On Sunday, March 16, the Minneapolis Star Tribune ran an article titled, "With no rules for crisis, Fed must improvise." No rules? How is it even possible that after more than two centuries of formal economic study, the field still has no "rules for crises"? Obviously, something deeply fundamental is awry; but if pressed for an answer, economists will respond virtually to the last man that the economic process is simply 'too complex;' that it is a system comprised of a vast number of different components with different functions, and that these are all inseparably bound up in an interlocking tangle of circular relationships.

However, there are very strong reasons to suspect that this may just possibly be an illusion. For the great failure of modern economics is in that it has been unable to identify a common denominator in order to pull it all together, for common denominators are absolutely irreplaceable as the sole means to integrate any seemingly disparate set of components into a cohesive, comprehensive and unified point of view.

Without a common center, the relationship of any given part to the whole must otherwise be analyzed as a basically independent factor; but at best --particularly since economics is permeated throughout by the nonlinear dynamics of feedback-- this approach merely creates an expanding web of unspeakably complex relationships. And this of course, is the modern experience. But a common denominator makes it possible to describe every facet of the economic process in terms of a common language, and the result is a completely unified point of view.

Now, the argument I've been advocating in each post --and which is actually very simple to prove-- is that this common denominator is energy --thus, "economics" is fundamentally a branch of applied physics. From this perspective it then becomes increasingly clear that study of economics simply made a bad beginning and became muddled very early on by mankind's almost universal fascination with money. Economic theorizing thus began with a small set of unquestioned assumptions surrounding money, trade and the nature of "value" as givens --when in reality, the dynamic nature and flow of energy in states of feedback has always been far more fundamental to the principles of the economic process.

Instead, given that money had value, and this value was designated in numerical terms, the study of economics did not really begin with any truly objective analysis, nor with any attempt to delineate its most fundamental nature by first simply tracing it back to its earliest possible point of origin. It began somewhere in the middle, already weighted with a syntax that was poorly adapted to the purpose of describing events in more fundamental and energetic terms, and it never recovered. Today however, we can make a fresh start simply by tracing the origin of the economic process back to the dawn of life itself; and in doing so, we come to clearly realize that the most fundamental source of economic "value" that ultimately maintains the value of our monetary system is, in and of itself, neither abstract nor subjective.

It has become a matter of faith for economists that money comprises the most fundamental essence of the modern economic process, even though in practice this simply doesn't really work. To understand why, imagine that physics was as widely studied as it is today, but no one had any concept for energy; that it had calculus, but without any underlying thread with which to balance and ground its equations. Under these circumstances, it could only describe phenomena in the most indirect, metaphorical and complex terms. Its descriptions of physical events would be inevitably disjointed and filled with inexplicable mysteries, unaccountable attributes, and paradoxes. Indeed, the more one tried to describe the whole, the more one would wander into a maze of complexity.

This is precisely what happened to the study of economics: it is a physics without roots.

So today, we have no choice but to hear Douglas Elmendorf, former Fed economist say: "Modern monetary policymaking puts a lot of weight on rules, but there is no rule book for an economic crises."

This is surely a completely absurd state of affairs, when all anyone really needs to do is to begin at the beginning --first, by observing the universal relationship of every consumer to food (a reiterative energy loop), and then recognizing just when this process must have begun. It then almost immediately pops into focus that the so-called "economics" of life is --and always has been-- nothing other than a circular, feedback energy process that has comprised the sole, unadorned essence of the economic process for eons; a cyclical phenomenon in which every consumer organism --from single-celled creatures to office workers-- is kept in a state of constant search for that which represents the essence of greatest "value": i.e. the energy in food.

It is a revealing thought experiment to just hypothetically subtract all of the potential energy from any given food source, because it then also becomes apparent that one is thereby also subtracting all of its "value." In other words, we see that "energy" and "value" --particularly in this instance, but also in a more universal sense as well-- are fundamentally interchangeable concepts. We can thus legitimately refer to economics as a "physics of value."

This same basic equation thus holds true for every other component of the economic process. Just look again at the underlying identity and common meaning hidden within such elements as work, fuel, tools (all based on the physics of energy forces), systems of tools (factories) in conjunction with labor, and last, but not least, money. Money, as we intuitively express it, is power.

But what is the energetic "value" of money? Money shares the same basic definition of any tool --in that it introduces a quantitatively higher level of efficiency into the economic process. By means of money, we don't have to carry lumber, corn or machine parts around on our backs in order to make a transaction. Its use thus effectively introduces the equivalent of more energy into the process, for here as everywhere, efficiency means less energy consumption.

Every aspect of the economic process, every product and service and transaction thus ultimately represents an energy value --even in the case of the (supposedly) completely abstract value of modern currencies. Every given component is either an energy source or an energy process or, as in the case of money, equivalent to an energy source, for the quite simple reason that "economics" is just an example of the messy physics of life.

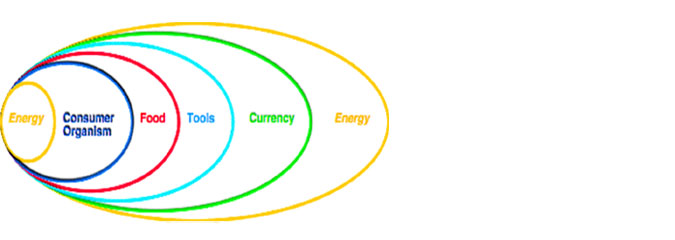

This is why "economics" is really just an unrecognized field of applied physics. It's an Energy System blanketed by a Money System. So by virtue of a now recognizable common denominator, we can proceed to integrate our explanations for economic events in terms of a common language, which then leads to the matter of engineering a completely unified and comprehensive economic system

In the process, we can now clearly see for the first time that the phenomenon of economic decline is basically nothing more mysterious than a decline in energy flow. It signifies that energy output, in terms of labor and/or food and/or fuel and/or energy generating technologies, is in decline due to an insufficient input. But this cannot be corrected by manipulating the money system, because varying the flow of capital by any means has no positive net effect on the economy at large, for the simple reason that its effective contribution --in terms of efficiency-- is already built into the system.

In other words, since the principles of monetary theory are based on a purely abstract concept of value --and not on any concrete physical essence-- today we find ourselves with an unstable economic system built on stilts. That is, on a purely psychological "trust standard," on "consumer confidence." In brief, on a very, very shaky foundation indeed.

Thus modern economics is deemed "complex" --and arguably schizophrenic-- but only as a consequence of the very perspective that maintains it in the first place, for its underlying reality is sublimely simple.

For the moment, the future is therefore a hairy prospect, but in spite of the looming potential abyss, it does not mean that we have to slide down the same slippery slope that ate the Soviet Union. For because our economy is a system --because it is an energy system; and because it is an energy system that is both represented by a tool and built upon the use of tools --the economy is, in and of itself an unrecognized and untapped technology.

This means that, as a technology for the production of energy --and as a process subject to clear and obvious engineering principles-- its potential for producing prosperity lies far beyond our accustomed norm. We merely need to start paying attention and rethink everything from scratch.

No comments:

Post a Comment